Investment Analyst Annabelle Miller looks at why Facebook and Google are such excellent franchises, and why this market power needs to be weighed up against their ability to sustain their long term social license to operate.

““Don’t be evil.” Googlers generally apply those words to how we serve our users. But “Don’t be Evil” is much more than that. Yes, it’s about providing our users unbiased access to information, focusing on their needs and giving them the best products and services that we can. But it’s also about doing the right thing more generally – following the law, acting honourably, and treating co-workers with courtesy and respect.”1

Google Code of Conduct until 2015

“Move fast and break things. Unless you are breaking stuff, you are not moving fast enough.”2

Facebook motto until 2014

These are the two cultural mottos that underpinned Google (Alphabet’s largest subsidiary) and Facebook’s building of giant businesses that, through their global duopoly in digital advertising3, have significant effects on the passage of information globally, producing economic, social and political power.

Google has 92% market share in search across all platforms4. Facebook has ~75% market share across mobile social media. This concentration of market power has meant that these two businesses accounted for close to 90% of the growth in digital advertising in 2018.

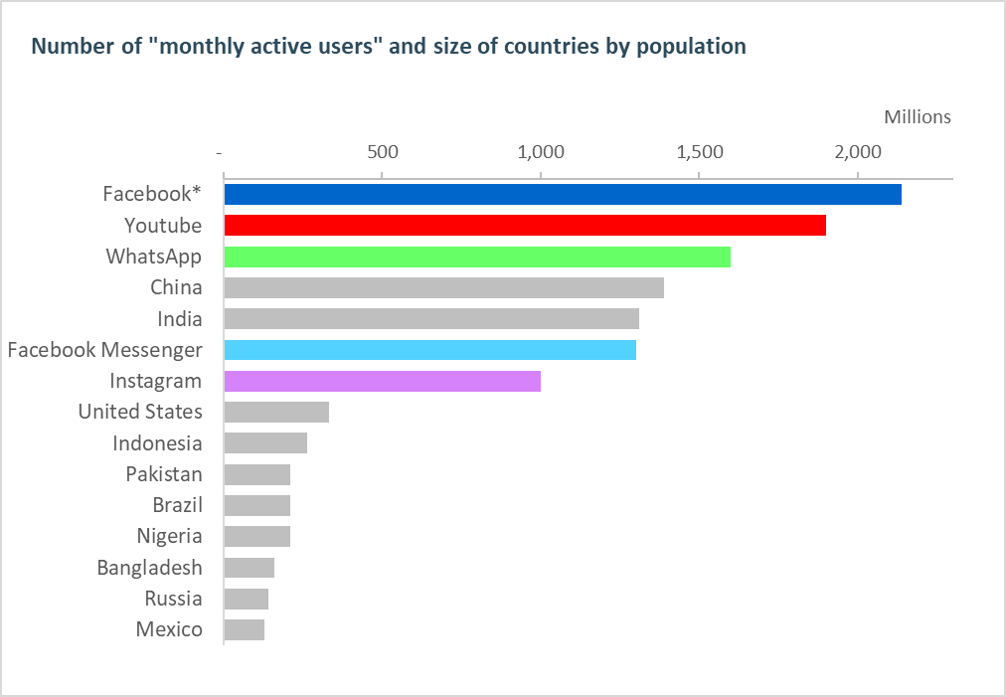

The power of these business models lies in the network effects generated from having daily user bases greater than one billion people. In fact, if Facebook users were gathered in a single country it would be the most populous in the world, given its 2.38 billion monthly active users. The more users engaging with the site, the more data that can be collected, the more value users are to a potential advertiser. Scale begets scale.

Source: (user data) https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ Ccountry data: https://www.census.gov/popclock/print.php?component=counter. Adjusted for ~10% of users that have multiple accounts.

They have become necessary social utilities. Some users called emergency services when Facebook recently went down6.

As investors we have cheered; we have been beneficiaries of the tremendous earnings power bestowed on these businesses by nature of the concentrated industry structure, enabling them to earn monopoly-type rents as evidenced by operating margins in excess of 25% for the core Google business and 40% for Facebook.7

As stewards of client capital, we view Google and Facebook as excellent franchises that have the ability to earn an above average return on capital over the long term. However, we must balance that with the economic and societal sustainability of how they earn their returns. From a pure market perspective, for example, there is some history of using antitrust laws in the US of breaking up powerful corporates – see AT&T and the Baby Bells in telecommunications and Standard Oil in the early 20th century.

These do not just include direct financial and valuation risks, but societal and industry-related trends and associated risks. We have to be wary of any future limitations that may be placed on these companies’ social licenses to operate, and therefore commensurate effects on valuations. In the trading session after the announcement that the Cambridge Analytica scandal had prompted slowing user growth (along with introduction of new European Union data protection legislation) FB’s share price fell 19%. 8 Notwithstanding this, in CY2018 total revenue rose 37% versus 2017.

Some issues relating to possible market failures are covered in an excellent book, The Myth of Capitalism, by Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn9. In it we learn about US Senator John Sherman, who in 1890 had a simple approach to market power:

“If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessities of life.10

Senator John Sherman

His approach led to the subsequent creation of the Sherman Act in the 1890s and sowed the seeds for the creation of the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission. These acts were described by Justice Thurgood Marshall, in a landmark judgement, as a form of Magna Carta for free enterprise:

“They are as important to the preservation of economic freedom and our free-enterprise system as the Bill of Rights is to the protection of our fundamental personal freedoms. And the freedom guaranteed each and every business, no matter how small, is the freedom to compete – to assert with vigor, imagination, devotion, and ingenuity whatever economic muscle it can muster.”11

Google has been fined twice by the European Commission for anti-competitive practices.12,13 Similarly, Facebook expects to be fined up to $US5 billion by the US Federal Trade Commission for breaching privacy violations.14

There remains considerable debate about how to best protect the consumer, promote competition but also enable these businesses to continue to innovate longer-term. The chorus of critics across regulatory and political spheres (rather than economic) spheres that argue the need to break up the tech giants in order to reduce their market power miss the bigger issues. Yes, it would reduce the market power of Google and Facebook, but it would not solve other issues confronted by Google and Facebook like the spread of abusive content on YouTube or the use of WhatsApp to propagate radicalism.

As shareholders we prefer management and regulatory bodies work together, producing a solution that preserves companies like Google and Facebook’s innovative engine, underpinned, as Justice Marshall put it, by vigour, imagination, devotion, and ingenuity. This will produce better products and services and also protect Google’s and Facebook’s social license to operate without significant and financially painful government intervention.

Following the terrorist attacks in Christchurch, Microsoft, Twitter, Facebook, Google and Amazon released a joint statement affirming their commitment to screening content that fuels hatred and extremism on their platforms. This agreement states five individual actions around terms of use, user reporting, technology, livestreaming and transparency reports. This is an encouraging step in forging a path of self-regulation by these companies, likely producing better long-term outcomes for users, society and shareholders15 and helping head off government fixes.

While Facebook and Google’s current outlook remains strong and we are happy to hold them, we remain vigilant about the economic, social and political implications of their market positions.

Would you like more insights? Subscribe below!

The mantra coined by Google engineers Paul Buchheit and Amit Patel in Google’s early days symbolised the core values the business culture was built on.

2. https://twitter.com/FastCompanySA/status/922719455418908672

3. Google has several products with duopolistic or oligopolistic positions, including a 75% market share in phone operating systems through Android and 60% market share of mobile browsers. http://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/worldwide

4. http://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share

5. http://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/mobile/worldwide

7. Company results ended full year 2018

9. Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn, The Myth of Capitalism – Monopolies and the Death of Competition, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2019)

10. Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn, The Myth of Capitalism – Monopolies and the Death of Competition, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2019) page 141

11. Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn, The Myth of Capitalism – Monopolies and the Death of Competition, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2019) page. 237

12. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-4581_en.htm

13. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-1770_en.htm

14. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/14/technology/facebook-ftc-settlement.html?module=inline

15. https://fbnewsroomus.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/christchurch-joint-statement-and-commitment-.pdf